Entry 03: Art in Fiction

Wolf Hall Trilogy by Hilary Mantel

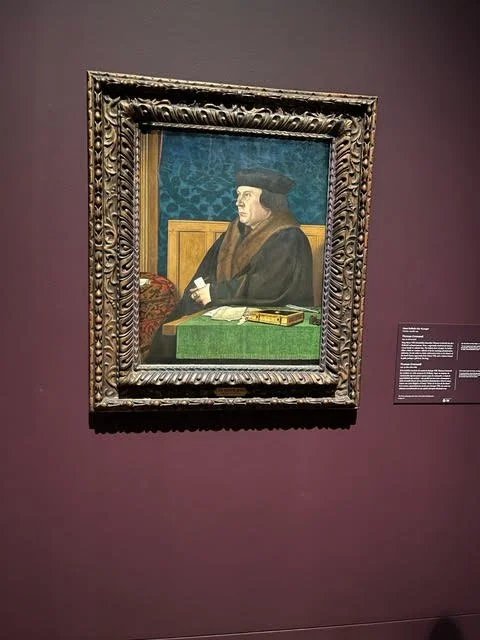

The day was a balmy 76 degrees in early January, when I caught the Hans Holbein exhibit at the Getty Center. The portrait of Thomas Cromwell, chancellor to Henry VIII, is smaller than I’d imagined, and brighter. As a fan of Mantel’s trilogy, I just had to see it, despite crowds, despite Omicron, despite leaving my kids at home. It did not disappoint.

Here’s Mantel describing her fictional Cromwell viewing his portrait for the first time:

He looks at the picture’s lower edge, and allows his gaze to creep upward.…

He sees his painted hand, resting on the desk before him, holding a paper

in a loose fist. It is uncanny as if he had been pulled apart, to look at himself

in sections, digit by digit. .. Hans had penned him in a little space, pushing

a heavy table to fasten him in. … He turns to the painting. “I fear Mark was

right.”

“Who is Mark?”

“A silly little boy who runs after George Boleyn. I once heard him say I

looked like a murderer.”

Gregory says, “Did you not know?”

Cromwell will, eventually, murder Mark. And George Boleyn. And George’s sister, too. Mantel’s astonishing feat is that she will persuade her readers to continue rooting for Cromwell. He doesn’t wield the blade himself, he unleashes a government apparatus to do the deeds. It’s no less brutal for all that, Henry VIII’s reign of executions features public dismemberment for the low-born, such as Mark, while aristocrats are granted private executions and intimate crowds. These government-sanctioned deeds are fulfilled at the King’s pleasure; the tension, of course, is that this King is so often displeased. Anything might set him off, and then heads, as they say, will roll.

I adore historical fiction and Mantel’s Cromwell trilogy is the fairest of them all. She reinvigorates a man, Cromwell, whose reputation had been cobwebbed and tattered for 500 years. She makes us reconsider him, dares us to admire him, makes us care. The Tudor period continues to fascinate (see the endless television, motion picture, and theatrical productions — the musical “Six” appears on Broadway as we speak), but can feel as stuffy as old, worn brocade in the wrong hands, ancient and far removed from modern concerns. The Tudors, of course, helped launch our modern world, and Mantel shows us how and why. Her people tease each other, bestowing snarky nicknames, giggling over ‘in’ jokes, sinking into gossip, or reverie, or wistfulness. Subject to Henry VIII’s imperious whims, their very lives are at stake. This is history fully juiced; it sizzles off the page. No wonder each separate book in Mantel’s trilogy won the Booker Prize for the respective year it was published — a historical feat in and of itself. The Wolf Hall trilogy is a masterwork. If the Holbein exhibit travels to a venue near you, it’s well worth seeing.

***** Highest Recommendation

2. Leaving The Atosha Station by Ben Lerner (2011)

I prefer Lerner’s sophomore effort, The Topeka School, to his fictional debut (he’s also a poet), but Leaving The Atosha Station has things to say about people and art. His drugged-out student protagonist bumbles through a fellowship in Madrid. His daily ritual, after getting baked, involves stumbling to the Prado where he positions himself before Roger Van der Weyden’s “Descent from the Cross.” Lerner writes: “Mary is forever falling to the ground in a faint; the blues of her robes are unsurpassed in Flemish painting. Her posture is almost an exact echo of Jesus’s; Nicodemus and a helper hold his apparently weightless body in the air.” But one morning someone else is parked in his spot. “I was about to abandon room 58 when the man broke suddenly into tears… I had long worried that I was incapable of having a profound experience of art…..” The narrator follows the man into gallery 56 where he “stood before Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” considered it calmly, then totally lost his shit.” Could such “triumphs of the spirit” genuinely move a man to tears? Throughout the novel — in conversation at a bar, at a poetry reading — the protagonist marvels that “everyone seemed to be having a profound experience of art.” He wonders whether its his poor Spanish that leaves him unaffected by the artful words others find so moving. The narrator no longer feels much of anything. What is art for? He isn’t sure. Only, when he thinks of a world without art he realizes that, confronted with such an eventuality, he “would swallow a bottle of white pills.” This novel portrays a young man abroad, stumbling through the process of self discovery.

*** Recommend.

See also: The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt; The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner; and others…