Entry 04: New Spins on Old Classics

New Spins on Old Classics: The Sixteenth of June by Maya Long

In The Sixteenth of June a wealthy, Joyce-obsessed urban couple celebrate Bloom’s Day by hosting an annual literary soiree. The patriarch, a self-made man, runs a vanity press. The Bloom’s Day bash includes banners, booze, and cocktail napkins with pithy quotations from the book. Just don’t expect to discuss the novel’s literary merits at the party. In Long’s novel, Joyce fandom is an empty gesture, a signal of aspirations and social anxiety. Is this running joke enough to hang a book on?

The trio of young protagonists — Nora, Leo, and Stephen — are quirky and well developed. Each are avoiding something: Nora, diagnosed with trichotillomania (a hair-pulling disorder), avoids therapy, avoids moving on with her life and pursuing her career in the wake of her mother’s death, and avoids setting a wedding date. Leo, her prospective groom, an affectionately-drawn ‘average guy,’ avoids realizing that Nora isn’t going to marry him. Stephen, Nora’s best friend and Leo’s brother, avoids his dissertation, avoids his loneliness, and avoids sexuality altogether. Asexual characters are rare in the literary canon; other than Hanya Yaraguchi’s A Little Life, I can’t think of many examples. There’s interesting ground to cover with this premise, of course, but it isn’t realized here. Unfortunately Stephen is so passive.

I’m not a Joyce scholar. In my twenties, I read Ulysees, and enjoyed it. A Bloomsday tour of Dublin one June 16th was a fantastic way to experience the city. The lemon soap, above, was purchased at a pharmacy dating to the turn of the last century. Of Finnegan’s Wake, I recall the opening, “riverrun,” and Joyce’s use of poetic language.

Ulysees begins with Leopold on the toilet; the scatological details proved shocking to readers at the turn of the twentieth century. The most famous section is Molly Bloom’s soliloquy at the end; Joyce was inspired by his soon to be wife, Nora, and wrote Molly as a full-blooded passionate woman: “ Yes i said, yes I will. Yes.”

Joyce was writing in a new, stream-of-conscious way about passion and real, lived experience in an era when no one said these parts out loud. Long writes about real, lived experience without passion — anomie is our modern condition. Passion is enjoyable to read about, anomie is a different reading experience altogether. Nevertheless, this is a strong debut novel; it takes risks, attempting to shine a light on areas that aren’t well represented in literature. I look forward to Long’s next book. **Recommend

2. Boy, Snow, Bird: A Novel by Helen Oyeyemi (2014)

Oyeyemi sets her novel in America in the midst of the twentieth century, and the first section of Boy, Snow, Bird is just wonderful. The second section switches to an adolescent character’s viewpoint, which disappointed me at first. Yet by the end, her choice makes sense. The POV character is the one we empathize with; both narrators take actions we come to understand.

Given that Boy, Snow, Bird reimagines Snow White, mirrors are an important theme, signaling concern with identity, what is revealed, what remains hidden. “Mirrors showed me that I was a girl with a white-blond pigtail hanging down over one shoulder; eyebrows and lashes the same color; still, near-black eyes; and one of those faces some people call ‘harsh’ and others call ‘fine-boned.’” Of course, there are worlds of information that mirrors cannot tell us.

After a dreary childhood with a rat-catcher father in a Manhattan ghetto (her mother having decamped long before), the narrator, a young woman named Boy Novak, sets out herself at age twenty, seeking a different life. She arrives in Flax Hill, “a town of specialists,” a town where everyone has a skill. After befriending the young women in her boardinghouse, Boy is introduced to Arturo Whitman, a widower with a young daughter named Snow. Arturo’s talent is as a jeweler. He presents Boy with a bracelet coiled like a snake instead of an engagement ring. “”[C]ould that scream ‘wicked stepmother’ any louder?” her friend asks. Boy replies, “I know.” Yet Boy comes to love Snow, Arturo’s beautiful, motherless daughter, which adds layers to this story that we think we know. There is jealousy at work, and a mother’s fierce desire, but Oyeyemi isn’t concerned with the cliche of a middle aged woman being upstaged by a young, fresher beauty. “[W]hen she and I are around each other, we’re giving each other something we’ve never had, or taking back something we’ve lost.” The scenes where Snow and Boy begin bonding are poignant. So why does Boy cast the young girl out?

Boy works in a book shop; there’s an interesting interlude where racial politics in the town come into play, which foreshadows the tensions that emerge in the book. When Boy and Arturo’s daughter is born, they name her Bird. In Section 2, Bird is the narrator, and she tells us “Sometimes mirrors can’t find me.” Members of previous generations, it follows, have made choices that complicate the lives of their descendants. Characters must reckon with their capacity to understand and forgive one another. In Oyeyemi’s tale, family relationships are every bit as fraught as those in fairytales. ***Recommend

3. A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley (2011)

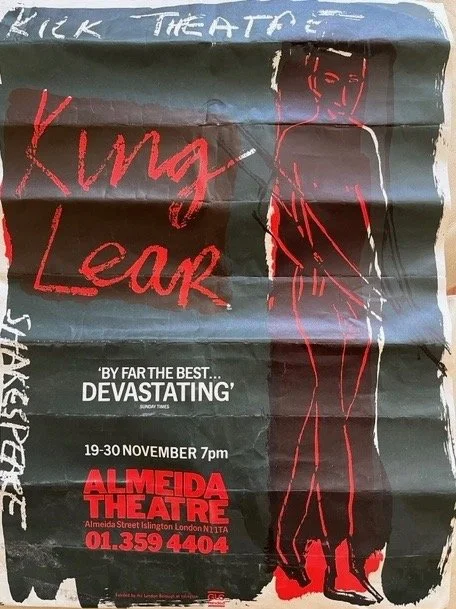

In the nineteen eighties I attended a performance of “King Lear” at London’s Almeida Theatre. This was a sparse, pared down, post-modern production, lacking a built set. Actors doubled up on roles — for example, Cordelia was also the Fool. Props consisted of a blanket, a pail of water, a stepladder and a skateboard. For the thunderstorm scene, someone balanced on the ladder and dumped the bucket of water on Lear, splashing the audience, too. It was riveting.

Smiley’s assured (and Pulitzer Prize-winning) reimagining of Lear hauls Shakespeare’s tale into the American midwest of the 1980’s, and it’s a marvel. The narrator, Ginny, looks back to her childhood, a time when acreage and financing were stand-ins for name and social standing. Her father accumulated a satisfying thousand acres of farmland, and in doing so, became a king of sorts. The original parcel of land had been in the family since the turn of the last century. Formerly swamp land, it has been tiled to draw the water and warm the soil, ideal conditions for abundant harvests and prosperity — for those who manage their affairs efficiently.

Flash forward to 1979 in Zebulon County, Iowa. Ginny, our narrator, and her older sister Rose, and their families, meet to celebrate the homecoming of a neighbor and close family friend. Even their youngest sister, Caroline, a busy lawyer in town, has come up from Des Moines for the event. The neighbor’s handsome prodigal son, Jess Clark, has returned after being drafted to fight in Vietnam and sheltering in Canada for thirteen years. Ginny, we learn, has been married to the well-mannered Ty for seventeen years but has no children; Rose has two girls but her charismatic husband occasionally beats her; in addition, she’s grappling with cancer. The host of the party, Harold Clark, has invested in a modern tractor, but how did he finance it? Amid the celebration and speculation, the girls’ father pulls his family together to announce his own plan: he’ll form a corporation and give his daughters shares in it, as a way of minimizing the inheritance taxes they’ll owe one day. The corporation will take out loans and expand their hog operation by investing in new equipment and building new facilities. What do they think?

- Good idea, Ginny replies.

- Great idea, Rose says.

- I don’t know, the lawyer, Caroline says.

- The father, who has had too much to drink, says, Fine, you don’t want it? You’re out. Thus the cracks in this family’s foundation appear. Ginny and Rose’s shared attraction to Jess Clark adds new fissures to Smiley’s carefully constructed setup.

For the remainder of the novel, Smiley’s characters flounder and flail, support one another, turn on one another (sue one another), fuel town gossip, in ways that echo Shakespeare’s story but make sense to the modern reader. Financial pressures and the whims of an aging, unreliable parent threaten the tenuous harmony these people have worked to maintain for so long. For in this family, feelings, history, and painful past events have been submerged and tiled over, like the saturated land they toil. This is a deeply satisfying and psychologically nuanced tale about dysfunctional families, the secrets they repress, and our American heritage. Highest Recommendation *****

4. The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter (1979, a collection of stories)

Fairytales with a feminist bent? Yes please! Carter’s reimagined fairytales captivated me in my early twenties; re-reading them proves they’re still great. Her writing, erotic, juicy, and irreverent, hits like a revelation. She was one of the first to wring modern, feminist sensibilities from well-known tales of yore. As Phillip Pullman says in his introduction to Fairy Tales From the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version (2012), “There is no psychology in a fairy tale. The characters have little interior life; their motives are clear and obvious…. The tale is far more interested in what happens to them, or in what they make happen, than in their individuality.… There is no imagery in fairy tales apart from the most obvious. As white as snow, as red as blood: that’s about it. Nor is there any close description of the natural world or of individuals. A forest is deep, the princess is beautiful, her hair is golden; there’s no need to say more.”

Angela Carter, driven by her appetite for more, spins the straw-stuffed shirt of fairy tales into gleaming literature. Her characters, all voiced in the first person “I,” possess an interior life. Her adjectives are plentiful, her descriptions vivid. “And, ah! his castle. The faery solitude of the place; with its turrets of misty blue, its courtyard, its spiked gate, his castle that lay on the very bosom of the sea with seabirds mewing about its attics….”

The eponymous story reimagines Blue Beard, that aristocratic serial killer who fascinates our dreams. His bride, seventeen, is a schoolgirl who leaves her mother (who has, we’re told, “outfaced a junkful of Chinese pirates, nursed a village through a visitation of the plague, shot a man-eating tiger with her own hand and all before she was as old as I”) for the groom, an older man with a streak of silver in his hair. She becomes his fourth wife; the bodies of her predecessors have not been found. He, of course, understands human nature. He knows to offer his bride all the keys to his palace…. but one. Holding up that one forbidden key while cautioning her against entering this one room — yet leaving that key to dangle temptingly on the ring with the others — he knows she’ll obsess over it. She can’t resist temptation. But Carter’s women aren’t helpless damsels. Their agency, their bad-assery, is a joy to behold.

Another strength of the collection is how the stories range in tone. “Puss In Boots,” funny and irreverent, told from the POV of the cat “I withdrew my head from my privates and fixed him with my most satiric smile…” (Yes, the “Shrek” screenwriters ripped this from Carter; Antonio Banderas aced it) to the elegiac, wistful “Erl King,” which explores a young woman’s sexual awakening, the push/pull of erotic desire. She longs to succumb; she worries that, in doing so, she’ll lose herself. “Your green eye is a reducing chamber,” the unnamed heroine addresses her lover. “If I look into it long enough, I will become as small as my own reflection, I will diminish to a point and vanish. I will be drawn down into that black whirlpool and be consumed by you. I shall become so small you can keep me in one of your osier cages and mock my loss of liberty.” Carter’s fairytales are lusty, imaginative, — and not for children. ****Highly Recommend

Jonathan Haig’s The Midnight Library, nods to Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, sending his protagonist, Nora, spinning through a range of different lives she might have led. A thoroughly enjoyable romp. ***Recommend. And of course, Charles Frazier’s Cold Mountain reimagines the tale of Odysseus, set during the American Civil War. ****Highly Recommend